publication Ribot gallery, Milano. text: Maria Villa, scroll down for english

THE FORMLESS, SOMETHING Talking about Siri Kollandsrud, by Luca Arnaudo, Equipéco 2009

In a very important late 1920s essay, Georges Bataille introduced in art the concept of the formless, “a term serving to render the concept of declassification, given that in general each thing is required to have its own form”. In contrast with the more reassuring and polished definitions very dear to science and philosophy at the time, the formless stormed in to represent a change, the presence of a violation. According to Rosalind Krauss, who has long been studying this issue, the formless is “the shading off of the edges around the rim”

Although placed into a very different historical and cultural background, far from the original field of Bataille, the concept of formless has not yet ceased to be of great importance. Rather it has taken on a further role of contrasting, not so much different conceptual categories, but the hardships typical of the latest unmonumental counterfeit, of confused uncertainty which governs the main exhibitions, or more directly, contemporary art experiences.

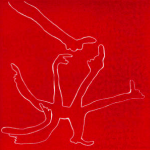

A similar line of discourse could also be applied to the work of Siri Kollandsrud, an artist of Norwegian origins who has long been actively working in Copenhagen and often spends time in Italy (her latest personal exhibition was held in Rome last December). The feeling of formlessness enters into every shape of her work, inspired by needs that we must not be afraid to describe as northern or feminine. In critical and spiritual support of this opinion we observe the moving generosity of both materials themselves and their combinations, definitely out of reach for any Mediterranean artist. Examples of this are the acid watercolours, the dark and at the same time shallow lightness of the linocut in which the generous bodies of women who clumsily carry a coffin on their shoulders give out first the idea of an amphibious blending of human limbs, then of the grand ceremonies of the power of the eye given by the cloth and the stain. In general this characterizes the entire body of the artist’s work, always hanging among

chthonic vibrations and minimal transfigurations.

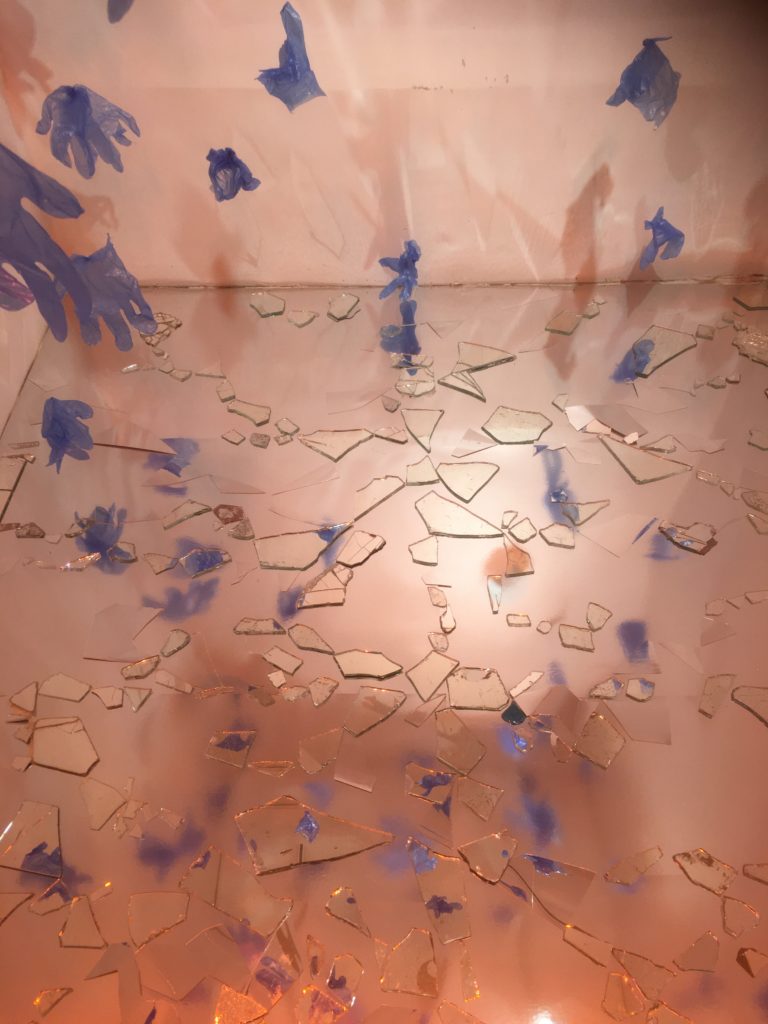

We were discussing the formless, which, if it must not be confused with the precarious, it does not even share the academic expressions of the informal. What we are witnessing here is rather an overabundant unity, the cellular proliferation of different things apparently in contrast with one another, similar to the soul’s cellar, where wood skein – statues pile up on drawings as gracious as a sketch, prints that emerge from the darkness of ink like dreams just before awakening. Fleeting installations of makeshift materials find and take on a meaning in their unity, permeated by a feeling of welcoming estrangement. Those who have never experienced the pleasure of hiding in the cellar, of being welcomed by dark masses of objects and memories that talk about themselves while whispering something else, are in this case very unlucky. Here, in other words, there is nothing, but at the same time something. As the artist herself puts it, it is the celebration of those moments in life when something indistinct happens, the formless in fact, which we do not notice, too busy as we are living day by day. It is a gift of colours, a dark party, and no longer definitions dictated by imagination, but tensions that lead to wonder.

Notes

Georges Bataille’s original theorization referred to in this article, was developed in the essay “The formless” (from the magazine Documents, n 7, 1929). Numerous essays have referred back to his theory. Among the most interesting and easiest to find are: Alessandra Voli “The formless image: Bataille, Warburg, Benjamin and the ghosts of tradition” (L’immagine informe: Bataille, Warburg, Benjamin e I fantasmi della tradizione). As for Rosalind Krauss, among the different works on the subject, see the Italian translation “L’originalità dell’avanguardia e altri miti modernisti, Fazi 2007. (“The originality of the avant-garde and other modern myths”)

That vital moment by Mai Misfeldt

If one considers Siri Kollandsrud’s paintings over a perjod of years, they ditfer somewhat in terms of colour scheme, structure and touch. But when one penetrates further into their universe, one finds that they are connected by a consistent, ever-questioning search. An open, inquisitive will to experiment her way forward, even when the way proves not to be the one immediately expected. Scepticism is not seen by our society as a positive quality, although doubt is in a reality a driving force. Only by taking one’s own scepticism seriously, by listening to its ever-challenging questions, one is pushed in earnest beyond the automatic processes which one, also as a painter, is all too wont to become addicted to.

Siri Kollandsrud’s work sticks to the retina like tracks left by alternating spontaneity and reflection. One could call it controlled coincidence -a sort of poetics for her painting. Coincidence in the sense that the artist has no preconceived sketch of w hat she intends to achieve; she has no finished picture in her mind toward which she works, the painting comes into being as she goes along, also as a result of a series of coincidences. Or like a collection of notes which gradually link together to form a whole. Controlled in the sense that, on the other hand, all that which crops up by coincidence is allowed to remain on the canvas. The decision-making processes lie in the painting as traces of a process. One could describe the painting process as perpetual negotiation and the painting itself as the book in which all the deeds are kept. A yellow stroke here to counterbalance a green one there. On her canvas, one colour calls up the next. A garish yellow in a corner provokes the eye and is slowly given a comb for its unruly locks, as other colours are drummed up against it. Laver is applied upon laver; decisions are made then regretted, painted over and wiped off. And then suddenly, the picture is finished and there is nothing more to add. The finished work is in itself a history of the process.

In art-historic terms, Siri Kollandsrud’s painting has its roots in abstract expressionism. Even so, expressionism is not the right word, because w hat we have here is not an artist’s desire to express herself through her paintings, so much as an urge to examine the figurative language that can be expressed through the expressive gesture of artistic composition. Of course, the impulses emanate from within, from within the artist’s consciousness, her sense perception and subconsciously as impressions. The impulses, however, also emerge while she is actually working on a painting,

as a sort of dialogue with the canvas, a dialogue that also has a capacity for humour.

Reference has also made of Kollandsrud’s work as “mental impressionism’. In the mean time, though, a form of surrealism has emerged, depending on whether more and more figures, organic, curled and almost amorphous shapes have forced their way into the composure of previous paintings. As far as the artist is concerned, it has to do with a concentration; a question of being there here and now and being loyal to w hat she has applied to her canvas. It is also about submission, of daring to let go and allow one’s brush a sort of automatism of the moment which afterwards is open to negotiation once more. So it is a question of balance between submitting remaining in control. Risks have to be taken if new ground is to be gained.

Whereas Kollandsrud’s paintings of a few years back were characterised by a tight, formal system in the form of grids, her new ones are open. Freshly sensuous and at times almost chaste. There is something pleasurable about Kollandsrud’s use of colour, where pink, mauve, yellow and a curious childish blue flow from her tubes, meeting in curly, cunningly playful shapes. Whereas Kollandsrud once worked with large, uniform surfaces, she now uses disharmonious, highly energetic encounters to a greater extent. Perhaps they are microcosms, but they could equally as well be patterns seen from some distance. The sensation of distance and a lack of distance at one and the same time is paradoxically confusing as well as seductive to the observer. Siri Kollandsrud seeks to achieve more than one thing at a time in her painting. Marked disparities can cause pictures to fall apart, but disparity can also establish dynamic tension. In Kollandsrud’s paintings it is the disparities, also between the immediate and the formal, which hold the picture steady. As observer you get the feeling that you have to look right now, otherwise you will miss that vital moment. It is right now that the point of balance shivers between standstill and rotation, attraction and repulsion, between submission and control. Right now that the picture quivers before your eyes, as a result of the meeting between blind somnambulistcertainty and vigilant challenging scepticism.

————–

Maj Misfeldt, Art critic, Berlingske Tidende